In breast cancer support spaces, Barbie jokes are frequent.

Women who have undergone a double mastectomy with breast implant reconstruction will often joke about achieving a newfound “Barbie status” – their now nipple-less breasts sit higher and perkier than ever before, thanks to implants, giving them a chest not unsimilar to Barbie, herself.

Some survivors celebrate their newfound “foobs” (fake boobs) – it is an important step to them becoming cancer-free, after all – but unlike elective breast removal or augmentation, these women often don’t have a choice in the matter. It’s a surgery attached to a disease that not one of them ever wished to be diagnosed with.

While it’s easy to see how these dark Barbie jokes resonate with this subset of the breast cancer population, what many do not realize is that a much larger group of breast cancer survivors have Barbie’s creator, Ruth Handler, to thank for helping them reconnect with their pre-cancer bodies.

I am one of those women benefitting from Handler’s legacy. A devastating phone call four-and-a-half years ago revealed that I had Stage 3 breast cancer, at the age of 36. A year later, I was diagnosed with a second breast cancer. One of the treatments I received, much like Handler, was the amputation of one breast.

Since my single mastectomy, there hasn’t been a day where I’ve not agonized over my body. I was not offered the option to reconstruct right away. My skin needed more time to heal from extensive radiation treatments and, anyway, the hospitals at the time were only doing the most urgent of surgeries due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

And while I do have the option to reconstruct my chest now, I’m delaying that decision for a while. I’m trying to put a bit of distance between myself and cancer. So, for now, I’m relying on a prosthetic breast to even out my chest and trying to not think about it too much.

However, I know that this time in my life, in this current iteration of my body, has been so much easier thanks to the work of Handler. To explain, I need to step back to Barbie’s origin.

“I’ve lived my life from breast to breast.”

For Handler, breasts came to dominate much of her life. So much so that she was known to say, “I’ve lived my life from breast to breast.”

In 1959, Handler revolutionized toy dolls when she introduced Barbara “Barbie” Millicent Roberts to the world. With her buxom C-cup and ample figure, Barbie was one of the first “grown-up” dolls to hit the retail market.

Handler wanted to create a toy that was different from the baby dolls that dominated little girls’ toy boxes. She wanted a doll that girls could project their future dreams upon and allowed for limitless clothing and career choices. Inspired by paper dolls of the time, Handler, to much controversy, made sure Barbie had the body of a grown woman.

“My own philosophy of Barbie,” Handler wrote in her autobiography, “was that through the doll, the little girl could be anything she wanted to be. Barbie always represented the fact that a woman had choices.”

And while people have derided Barbie for years over her physical attributes – her blondeness, thinness and whiteness have been called out just as often as her large breasts – Handler would go on to revolutionize prosthetic breasts for people who had lost theirs due to cancer.

A devastating diagnosis

- Poilievre calls supervised consumption sites ‘drug dens,’ vows to close some

- Poilievre calls Trudeau a ‘joke’ on world stage, won’t commit to NATO timeline

- How Project 2025 could upend Canada-U.S. relationship under Trump

- Beryl aftermath: Child dead after flash flooding in N.S., victim found in ditch

In 1970, while serving as CEO of Mattel, Handler was diagnosed with breast cancer. While feminists were lambasting Barbie for the doll’s anatomically unfeasible bust/hip/waist ratio, Handler was secretly receiving treatment for breast cancer. She underwent a single mastectomy, having her left breast removed in her path to becoming cancer-free.

While Handler remained at the helm of Mattel for several years following her diagnosis and amputation, she and her husband were pushed out of the company in 1975 after federal investigators launched a probe into the company’s then-faltering finances.

Once out at Mattel, she pivoted back to breasts, although this time she focused on the chests of real women.

“I had been fighting to be a respected female executive all my life, and when I lost my breast it was as if I had lost my femininity,” she told CBS News in 1994.

At the time, however, there were very few options for non-surgical alternatives to breast reconstruction. Women who opted for either a single or double mastectomy were resigned to stuffing their bras with socks, tissue or fabric breast prosthetics in a feeble attempt to recreate the look of breasts or balance out their remaining breast.

These artificial breasts, too, were used interchangeably for the right or left side, making it pretty much impossible to achieve a natural looking chest.

“They were designed by men who obviously didn’t have to wear the damn thing. And, besides that, they didn’t match the other side. The two sides just didn’t match,” she explained.

With a newfound determination to empower women, once again, Handler set out to create what would eventually grow become another multi-million dollar business – a realistic looking and feeling breast prosthesis.

While women before her had attempted to create a breast form that had a more natural aesthetic, many forms had design drawbacks. Some required special belts or bands to keep them in place. Others didn’t hold up in water, making them inadequate for activities like swimming. Depending on the materials used, some lacked proper ventilation, making them a nightmare on the skin, while others could become dented or were difficult to clean.

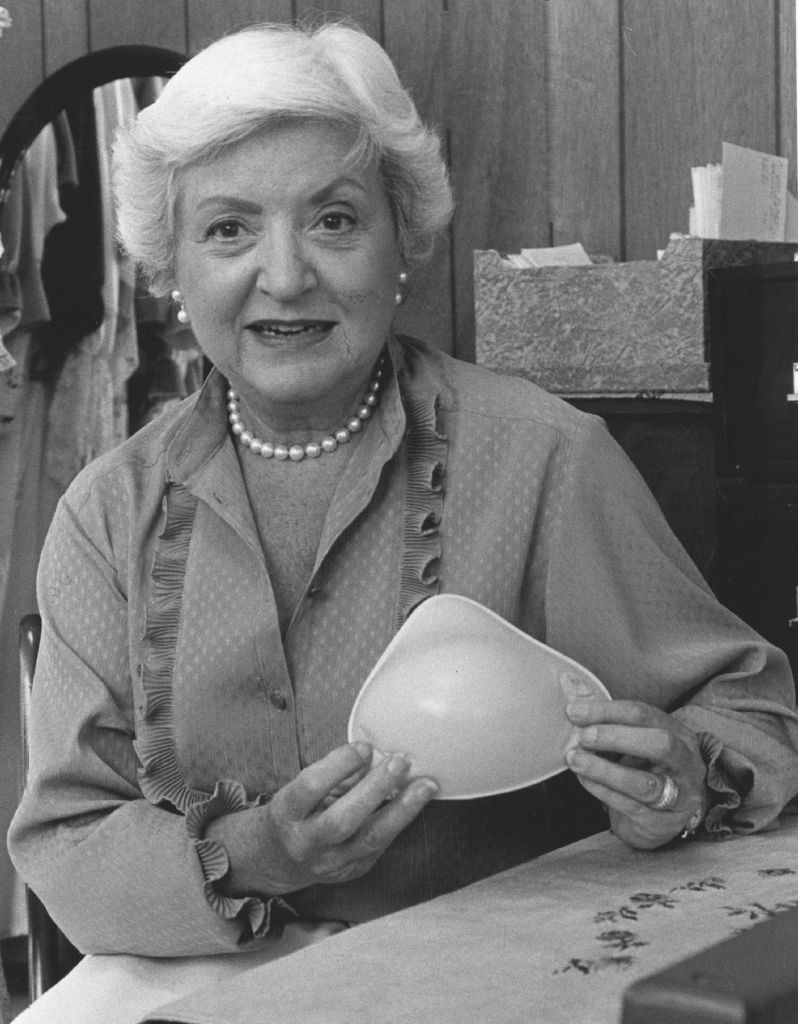

Handler, however, had a solution. Looking at the popularity of silicone breast implants, she set out to create the world’s first liquid silicone breast form that was meant to fit into a bra, rather than under the skin. While she was at it, she gave women the ability to choose from a customized right or left breast.

“The emphasis on breasts in our society is so large that sometimes a woman’s image of herself, how sexy she is, how beautiful she is, depends on her breasts. I felt this, when my own breast was gone, that I was less than a woman. I had to find a way to get a better self-image,” Handler told The New York Times, reports Women’s Health.

Within five years of creating the Nearly Me breast prosthesis, sales of the forms had surpassed US$1 million. Handler travelled the country, selling her prosthetics, sharing her story and connecting with other cancer survivors.

With the same gusto with which she developed Barbie, she opened the world’s eyes to the psychosocial benefits of breast prosthetics – although her bold tactics would sometimes raise eyebrows.

In the CBS interview from 1994, footage shows Handler standing in front of a convention audience with her blouse hanging open. Another clip shows her inviting a journalist to touch her breasts, asking him to guess while breast is real and which is fake.

Barbie helped my emotional healing

Pre-cancer, my relationship with Barbie was a complicated one. As a kid born in the 80s, it was impossible to escape the rhetoric of “Barbie as a bad role model” and, admittedly, I bought into a lot of it.

So, when my daughter, who was two-years-old at the time, started to show an interest Barbies shortly after my cancer diagnosis, I was conflicted. I didn’t want her to play with a toy that would damage her self-esteem or limit her aspirations, let alone one that looked so distant from her bald, disfigured mother.

Researching Barbie options, however, opened my eyes to just how far Barbie has come in the years since I was a kid. She’s now the most diverse doll on the market, and comes in a wide range of shapes, sizes and colours. Barbies on store shelves today have vitiligo, Down Syndrome, hearing aids, and use prosthetic limbs.

There’s even a Barbie for cancer patients – Brave Barbie – a partnership between Mattel and CureSearch that sends a bald Barbie to families affected by cancer.

Gifting my daughter a cancer-afflicted Barbie was tremendous. We would play with that Barbie together and I’d heartbreakingly watch her pretend to take the doll to the hospital for chemo, or place its long wig on top of its head and tell the doll “it’s time to be beautiful again.”

But that Barbie also allowed me to project through play other takeaways to my daughter – and in many ways to myself – that were otherwise difficult to talk about or explain.

Bald Barbie was super brave and went on awesome adventures after chemo. Sometimes she felt sick and needed to sleep, but would feel much better after a rest. Bald Barbie always beat the cancer and went on to live a long and happy life with her family.

That Barbie became so much more than a plastic doll – she was a conduit for communication and a coping mechanism during an extremely distressing time for our little family.

Now, as my family moves farther from my cancer diagnosis, Brave Barbie has been put back in her box and my daughter has moved on to other dolls.

But I continue to hold Handler’s legacy close to my heart, quite literally.

Confidence in my chest

The first time I watched the clip of Handler inviting a talk-show host to feel her up, I laughed out loud. Much like Handler, I have invited curious friends to compare my one natural breast to the prosthetic.

I don’t fault anyone for being curious. In the right clothes, my prosthetic breast is undetectable. The symmetry is precise and the movement is natural. When I’m wearing my prosthesis, it’s virtually impossible to tell that I only have one natural breast. Acquaintances who aren’t as familiar with my cancer story will often ask me when I had reconstruction and how it went.

Handler passed away in 2002, but Nearly Me continues to make breast prostheses. I wear a different brand, only because it was what was available when I went for my fitting shortly after my mastectomy surgery, but the design, shape and materials used to make the prosthetic that sits inside my bra is owed to Handler’s ingenuity and pioneering spirit.

“When I conceived Barbie, I believed it was important to a little girl’s self-esteem to play with a doll that has breasts. Now I find it even more important to return that self-esteem to women who have lost theirs,” a 1995 New York Times article quoted Handler.

Accepting my post-cancer body is not easy and I struggle with it every day. Living with one breast is difficult – I don’t always get to wear the clothes I want, public change rooms are a minefield of awkward looks and loud declarations from curious kids and I’m reminded of cancer every time I get undressed.

Maybe, one day, I will choose to reconstruct my breast or have the other one removed for symmetry.

But for now I will thank Handler, her Barbies and her prosthetics, for being important tools in my breast cancer healing.

Comments